How do you run an authentic, progressive, populist campaign that empowers grassroots activists across a state as geographically, occupationally, and (occasionally) ethnically diverse as Minnesota?

Go to Northfield to find the answer.

Well, not ONLY Northfield, but it’s a good start.

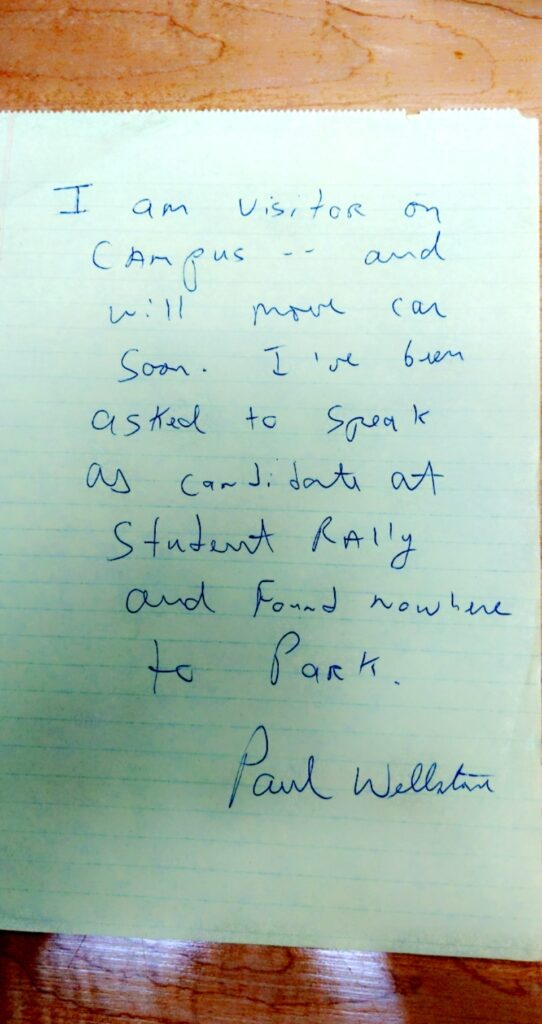

That’s because Northfield’s Carleton College was, in the 1970s and 1980s, home to political science professor Paul Wellstone, perhaps an unlikely figure to become a U.S. Senator from the state of Minnesota if you only consider his appearance: a short, rumpled, curly-haired Jewish professor with multiple arrests for acts of civil disobedience.

That information alone isn’t terribly new, nor is the rejoinder that Wellstone overcame that shortcoming with a dogged belief that “good public policy, grassroots organizing, and electoral politics” could transform the American political system, from his role in the “Power Line Fight” of west-central Minnesota to his sit-in at the First State Bank of Paynesville and his marching with strikers at the Austin Hormel plant in 1985-86 to his chairing Jesse Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign in Minnesota. Wellstone’s biographer Bill Lofy, his campaign biographers Dennis McGrath and Dane Smith, and Wellstone’s own The Conscience of a Liberal spell out Wellstone’s beliefs, and you can read Wellstone’s account of the power line fight or his first experience organizing in Minnesota, How the Rural Poor Got Power, about organizing with the Organization for a Better Rice County in a southeastern Minnesota county centered on Faribault. Even Ryan Grim’s We’ve Got People has connected Wellstone to the “progressive populist” tradition of Jesse Jackson and, yes, Bernie Sanders.

So what more is there that can be said?

Since my dissertation years, one of the core questions I have been exploring has been the relationships between these “progressive populist” senators–the Wellstones, Harkins, and Feingolds of the world–and their state Democratic(-Farmer-Labor) parties and their states’ political history. How did they relate to the party’s state central committee? Were their campaign arms separate or welcomed, coordinated or at odds? How did they talk about the political traditions of Floyd Olson or Robert La Follette, if at all, and did it matter?

Follow @Cory_HaalaResearch

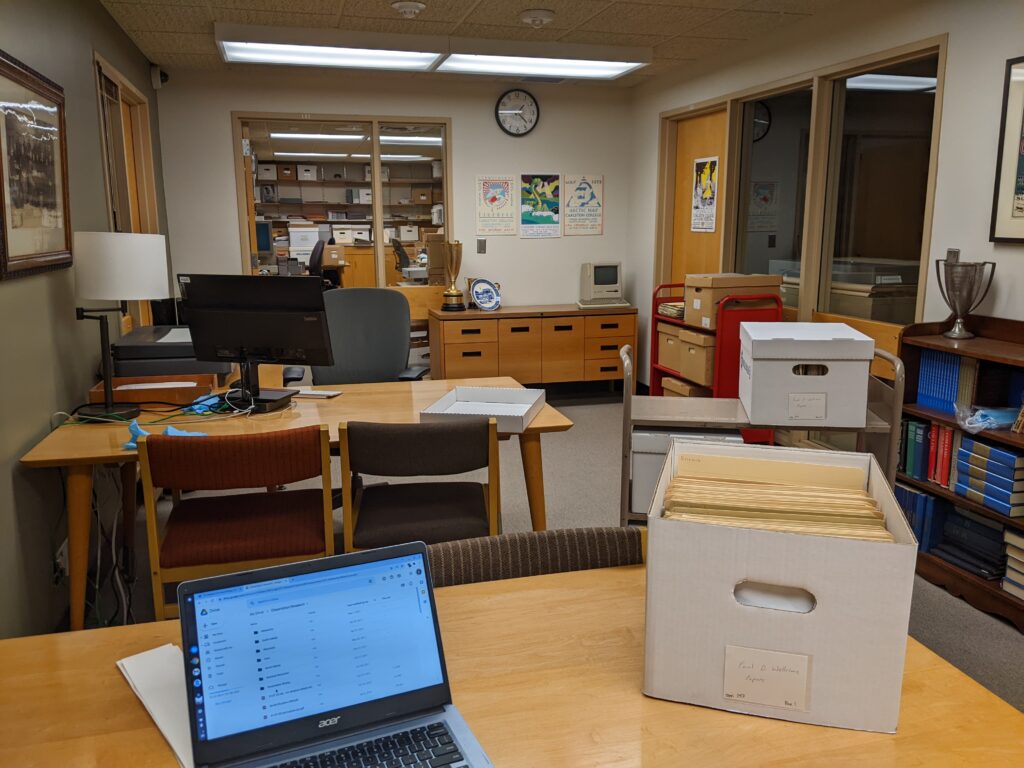

These short-term trips to Northfield (over Spring Break and as their fantastic archivist, Tom Lamb, was available this summer, etc.) poked at a number of those questions for a few ongoing projects: a chapter I’m editing on progressive farm organizing and policy-making in the 1980s, an article on Wellstone’s involvement with a voter registration drive called the 33% Campaign, and my manuscript-in-progress.

(This blogging is clearing the pipes after a little vacation so I’m ready to write again.)

The Collections

- Paul Wellstone Papers (90%)

- Barry Casper Papers (10%)

These are particularly valuable to me, because while the bulk of Wellstone’s campaign records are held at the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul, they are seemingly under lock and key until at least October 25, 2022, the twenty-year anniversary of Wellstone’s untimely death in a plane crash while campaigning for reelection. Usually, in the case of the papers of Minnesota congressman Tim Penny or Jesse Jackson campaign consultant Janis Pryor, I have been able to petition the owners for access to their records.

Not so with Wellstone.

That’s not for lack of trying — MNHS staff have responded to my emails, a couple folks who knew Wellstone have been gracious to share their memories via phone, and Paul’s son David even wrote the MNHS on my behalf, requesting they grant me access to the papers. I’ve emailed former Wellstone Action Foundation members. I’ve reached out to his former campaign manager.

No dice.

Whether these records are simply closed until October 25, 2022, regardless of who asks, held by some of the former “Wellstone for Senate” chairmen, or caught up in the change of the Wellstone Action Foundation to re:power, it’s been a frustrating run-around. Instead, these Wellstone papers at Carleton have helped me not only piece together some of what made him unique, but unearth a few stories particularly relevant to the political culture of the Upper Midwest and how Wellstone fought with the establishment structure of the DFL (and, of course, won The Wellstone Way).

In the meantime, it was a real pleasure to get back to Carleton College, walk the campus in both mid-March and late June, and be at home on the kind of small liberal arts campus that I really love.

The Findings

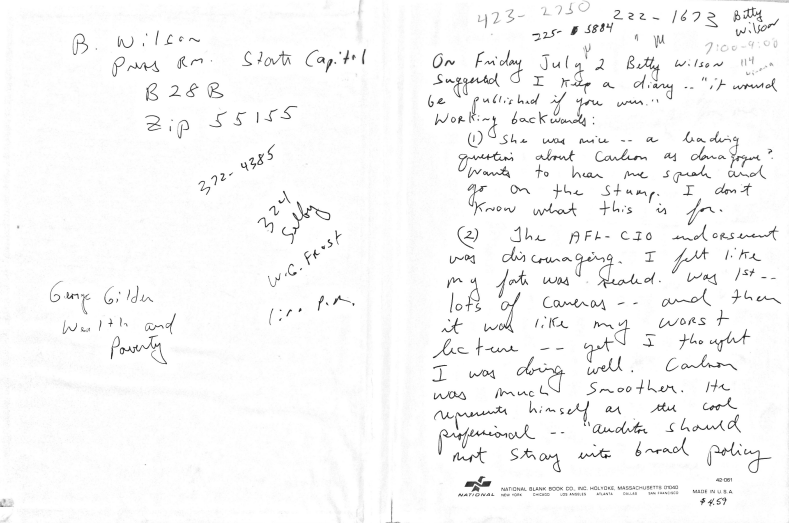

Wellstone’s 1982 Auditor campaign was a turning point. While Wellstone had been involved in politics through OBRC and the power line fight, he had also begun to dabble in DFL politics, first as a member of a left-wing group called the Farmer-Labor Association (FLA) and then the DFL Party itself. Linking up these groups with party politics is important to understanding Wellstone’s 1990 victory but also the political history of the grassroots left: Wellstone serving on the FLA’s Farmer Labor Education Committee as one of its three board members in 1981, crediting the FLA and Minnesota Citizens Organized Acting Together (COACT) with his relative success in 1982, or hailing the work of COACT and the progressive Northern Sun Alliance while giving a support speech for U.S. Senate candidate Mark Dayton (yes, that Mark Dayton) in July 1982. His papers, especially a campaign diary he kept at the suggestion of Betty Wilson of the Pioneer Press, show his political maturation in real-time.1

The diary, in particular, revealed some of the lessons Wellstone learned along the way: writing “I feel empty” after at first failing to win a labor endorsement, recalling annoyance with the “smooth, self-important rich people” at a fundraiser hosted by DFL Senate Majority Leader Roger Moe, and in his election takeaways noting he needed to work with the “DFL as a machine.”2 Nonetheless, Wellstone committed to running his campaign–and continually learning how to define and present himself–as a “progressive populist”:

Organizing and campaigning with a foot in both camps. COACT director John Musick thanked Wellstone for making the nuclear freeze, labor movement, and community organizing part of his Auditor campaign (despite those things not being part of the Auditor job itself): “It took a lot of courage to raise the issues you did. You took a lot of flak for it, but I want you to know that all of us in ‘the Movement’ have benefitted greatly from what you did.” Over the next eight years, Wellstone became a bridge between “the Movement” and the DFL. While working as an adviser to Gov. Rudy Perpich, Wellstone led the DFL Education Committee, heartened after one dinner in rural Redwood County in 1983 that “this education program could really catch on.” He stood with strikers at Hormel in Austin, a year after Groundswell organizer Bobbi Polzine leaned on him to attend the Farm Crisis rally at the Minnesota State Capitol in January 1985, and praised Iowa farm advocate Dixon Terry (“a hero to me”) at a speech to the Iowa Democratic Party in 1997.3

This was a feature of Wellstone’s organizing: after the massive Democratic defeats of 1984, he chided the party about running telegenic candidates and relying at the national level on superdelegates. Instead, he believed, the party “should link up some legislators, policy/research people, and the grassroots constituency groups, come up with several powerful themes…and hammer away for the next two years, four years.”4

Broaden the tent. Wellstone sought to do this in both voter registration and in policy-making. One of the things I was really surprised to learn on this research trip was that Wellstone had represented grassroots farm advocates and helped write the Harkin-Gephardt Farm Policy Reform Act of 1987. But he also sought low-income and disillusioned voters while leading the Minnesota 33% Campaign in 1986, working from the idea, developed after the 1984 elections, that “over one-quarter of the population fails to vote in any single election,” and “many of these nonvoters are low income citizens whose circumstances are not reflected in the current political culture and policy options.” Wellstone and a team of volunteers, many of them former students from Carleton, worked to register voters at food banks and welfare offices in the fall of 1986. After some setbacks (you’ll have to wait for the article for those), Wellstone hoped “a 5% enlargement of the electorate from this segment of the population is not an unreasonable goal in 1990.”5

Little surprise, then, that after the DFL successes of 1986, folks began to approach Wellstone about running for Senate. That December, though, he confided a hypothetical progressive campaign for the Senate could work only…

If: it captured the imagination of the media well before convention and provided us with forum to introduce important perspectives into political dialogue of Minnesota, the candidate was able to receive at least 45% of vote on first ballot at convention, progressive people would leave convention feeling good and determined to organize around the peace/economic justice issues and a strong force in the DFL………

Finally, Wellstone concluded, “Maybe all this is possible.”6

Build the party. “As much as I appreciated all that Governor Rudy Perpich did–and I like him a lot,” Wellstone told then DFL Education Foundation president Amy Klobuchar (where did you think she got the green bus idea from?) after his electoral upset in 1990, “he never was that interested in the party. I’m really interested in the party; I came from the party.” Wellstone had rejected a third-party campaign in the style of activist Polly Mann’s 1988 bid for the U.S. Senate, and instead made good on a promise before he even ran for Auditor in 1982: “I am going to condemn in no uncertain terms the Reagan military-defense budget and help build a grassroots education program [emphasis added] about the insanity of nuclear war and the ways in which the spiraling arms race drains our state economy.”7

That’s not to say everyone believed in him. The DFL State Convention Nominating Committee did not report his nomination to the Democratic National Convention in 1988 as some unwritten retaliation for his co-chairing of Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign and Wellstone’s outspokenness. But, after his 1990 victory, DFL adviser D.J. Leary wrote him and apologized: “I cannot tell you how ashamed I am that I was not one of your public supporters much earlier… Your commitment to caring about the things that have stirred my passions over those years–young people, Indian people, the disenfranchised and the disabled–has aroused in me a new sense of hope that I haven’t known since Senator Humphrey died.”8

A pickup truck, or a green bus? Wellstone originally conceived of his green bus as a “populist ‘pickup truck’ campaign,” but thanks to some brainstorming from Carleton professors like his friend and co-author Barry Casper, a green bus picked from a Highway 3 bus barn was the winner:

Nothing would better symbolize the ‘take-it-to-the-people’ approach and progressive-populist message, utilize Paul’s stump-seaking gifts and get him out around the state in a way guaranteed to attract attention than a whistle-stop campaign waged from the back platform of a green and white bus with Paul’s farm-to-city logo on the side.

Mike Casper, “Some Thoughts About a Press Strategy for the Wellstone Campaign,” n.d., 2. Casper Papers, Box 8.

It became the symbol of his campaign, with the help of slick TV spots from North Woods Advertising.

That’s all, more broadly, part of a real commitment to not just the progressive populism of the 1980s, but the progressive populist tradition of the Upper Midwest, that’s there throughout Wellstone’s writings. Wellstone was, as he liked to put it, “from the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party.”

But he was also part of a movement that elected its own to political office. From attending conferences on populism to reading about the history of North Dakota and describing “progressive-populist” campaign strategies to weighing in on the 1992 presidential campaign, Wellstone and the grassroots movement he joined navigated the “outsider-insider” status of populists in Democratic politics.

The City

Because I was just driving from Crystal down to Northfield, I didn’t spend a night out on the town, eating and drinking at a bunch of the local spots. In fact, outside one trip to a brewery in 2019, I had only been to Northfield one other time since high school (Carleton was one of the two colleges to admit me, though I didn’t attend) — a surprise as I reflected on it, since I grew up in Inver Grove Heights, just 45 minutes north on Minnesota Highway 3. I did have a really good pizza from B & L’s, but more often I had time to stop for a pint or a crowler at a local brewery before I headed home:

The Beer

The brewery I first visited in 2019 and came back to on this research trip was Tanzenwald Brewing Co. I’m a sucker for a doppelbock, and so their Tanzenator was right up my alley.

Their Hitthebrix, a Belgian golden ale, was a little on the bubblegum-tasting for me (I do realize that’s the point, etc., just not my thing), but the Gottlieb Bavarian pils was a nice palate-cleanser before I hit the road. Flavors of lemon and pepper that I really enjoyed. In the meantime, I’m kicking myself for not getting the Another Brix in the Wall, the barrel-aged sour with cherry.

Happens to be my brand.

It was just after 3pm at Tanzenwald, right when they’d opened, so I didn’t get a huge idea of what the brewery’s atmosphere was like. I enjoyed Tanzenwald and would love to come back to try their food sometime, but Imminent Brewing across town caught my attention for different reasons: they were showing a West Ham game!

The Irons are my favorite team in the English Premier League, and their Europa League match was only available on a Spanish-language channel, but Imminent had it on anyway because one of the bartenders (whose name I’m forgetting…but thank-you to him!) is a West Ham fan. Their Zombie Pom Sour was fantastic, and Low Rider Lenny’s Stout had a really sweet finish after a malty, roasty start.

There was a much more laid-back vibe in Imminent that I really enjoyed, and the brewery looked

One last spot Laura and I had stopped in the summer of 2021 was a couple miles south of Northfield, in Dundas, at Chapel Brewing:

Their kölsch was nice and crisp, of course, and I had a crowler of their Cherry Quad that married some of the caramely quad flavors with one of my favorite adjuncts in cherry. For my money, though, the Dukes Pilsner was a really grassy, refreshing beer for summer drinking. And, since it’s brewed in conjunction with the local town ball baseball team, it’s got small-town Minnesota written all over it.

What’s Next

As I mentioned earlier, this post is helping me clear the pipes as I prep a few works in progress. I’m editing a chapter on progressive farm policy for an edited anthology, am moving to review on my book (my tentative title, likely to be changed for the better by the press: How Democrats Won the Heartland), and have articles in progress on some anti-NAFTA organizing in the 1990s Midwest and the Wellstone material you read above.

I was fortunate to spend the 2021-22 school year teaching in the Honors College at the University of Houston (including a class on populism in U.S. politics); while I’m disappointed to not be back there this fall, I’m looking forward to new opportunities closer to home!

Enjoying these updates? Keep in touch with all my travels and research on Twitter @Cory_Haala.

Past Trips: Where I’ve Been

Pierre

Iowa City

Bloomington

St. Paul, St. Cloud

Menomonie

Milwaukee

Iron Range, Lake Vermilion Edition

Grand Forks

River Falls

Iron Range, Biwabik Edition

Bismarck-Mandan

Des Moines

Fargo-Moorhead

Stevens Point

Carbondale

Ames

Boston

Watertown, Brookings, and Aberdeen

1 “Board of Directors Minutes,” Farmer Labor Education Committee, January 2, 1981. Box 1, Al Wroblewski Papers, Minnesota Historical Society; Paul Wellstone, “Support Speech for Mark Dayton,” Worthington, MN, July 21, 1982, 1-2; Sam Delson, “State auditor race a hot one,” In These Times, October 6-12, 1982, 7-8. Both found in Box 2, Folder “State Auditor Campaign,” Paul Wellstone Papers, Carleton College. Hereafter referred to as Wellstone Papers.

2 Wellstone campaign diary, c. 1982, 2-3, 37. Found in Wellstone Papers, Box 1.

3 John Musick (COACT) to Paul Wellstone, December 9, 1982, 2. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Loose Papers [2]”; Wellstone campaign diary, 39, 51; Paul Wellstone, “Speech to Iowa Democratic Party,” June 28, 1997, 1. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Iowa Democratic Party, 1997”.

4 Paul Wellstone, letter dated December 5, c. 1984, 1-2. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Notes and Memorabilia”.

5 “Paul David Wellstone: Candidate for United States Senate from Minnesota,” c. 1989, 2, 4; Draft of paper, Paul Wellstone, c. 1984-85, 2.

6 Paul Wellstone, letter postmarked December 11, 1986, 1. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Loose Papers [2]”.

7 Amy Klobuchar, Ross Corson, and Paul Wellstone, “Interview with Paul Wellstone: A Different Kind of Senator,” IDEA News, DFL Education Foundation (Fall-Winter 1990): 7. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Loose Papers [4]”; Nicholas Pilugin, “And the Winner Is…?” Twin Cities Reader, June 21-27, 1989, 1, 8-11; Paul Wellstone, letter dated March 4, 1982, 1-2. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “State Auditor Campaign”.

8 Pilugin, “And the Winner Is…?”, 8; D.J. Leary to Paul Wellstone, November 12, 1990, 1. Wellstone Papers, Box 1, Folder “Letters [1]”.