How do you run an authentic, progressive, populist campaign that empowers grassroots activists across a state as geographically, occupationally, and (occasionally) ethnically diverse as Minnesota?

Go to Northfield to find the answer.

Can Left-Wing Populism Win in Democratic Politics?

I joined the podcast “The Same, but Worse” to answer a few questions with burning relevance to modern American politics: What is “progressive populism?” How did Midwesterners respond to the economic challenges of the Farm Crisis and deindustralization in the 1980s? And, of course, which states are in the Midwest?

Continue reading “Can Left-Wing Populism Win in Democratic Politics?”Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Biwabik Edition

While my last trip to the Iron Range was doubly-immersive, acclimatizing to both the politics and the culture of Minnesota’s Northeast, this one took on more of a “business trip” feel. This was both good, because I explored the deteriorating relationship between Perpich and the DFL, and frustrating, because it provided fewer outlets when things really got confusing.

Continue reading “Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Biwabik Edition”

Rural Democrats? Don’t call it a comeback.

The 2016 elections, in addition to making what I am trying to get a PhD in about 100x more relevant than I ever could have done myself, have also led to a very, very obnoxious trend among national political outlets: a newfound fascination with rural or agriculturally-oriented Democratic interests, groups, and politicians.

Take, for example, the Washington Post‘s breathless exploration in November 2016 of “Why rural voters don’t vote Democratic anymore,” in which they suddenly rediscover Collin Peterson (DFL-MN7). In the article, Peterson notes that

Donald Trump owes his victory to rural voters who feel they’ve been abandoned by a Democratic Party that has become increasingly urban and liberal.

and that

We have become a party of assembling all these different groups, the women’s caucus and the black caucus and the Hispanic caucus and the lesbian-gay-transgender caucus and so forth, and that doesn’t relate to people out in rural America. The party’s become an urban party, and they don’t get rural America. They don’t get agriculture.

While not nearly offensive as the New York Times’ ridiculous exhortation to “Go Midwest, Young Hipster,” it is incredible to finally read a profile of Peterson, who was first elected to Congress when I was one month old.

Now, just this morning, rural interests in the Democratic Party have caught Politico‘s eye. Looking ahead to Tammy Baldwin’s 2018 reelection defense, not only the media but, inexplicably, the Wisconsin Democratic Party itself appears caught off guard by the fact that there’s a rural interest it needs to pay attention to:

The Wisconsin Democratic Party has already hired five outreach coordinators specifically focused on rural counties, ahead of Baldwin’s first reelection run and the 2018 gubernatorial race in the state.

Amusingly, I spent a few hours over 2 days at the Midwestern History Assocation Conference and Agricultural History Society meeting in Grand Rapids talking about this exact thing! There is suddenly renewed interest among national commentators in the rural (and especially Midwestern) Democrat, yet U.S. Representatives like Tim Johnson (D-SD), Dave Obey (D-WI), Tim Penny (then*-DFL-MN), Kent Conrad (DNPL-ND), Neal Smith (D-Iowa), and others, along with U.S. Senators like Tom Daschle (D-SD), Byron Dorgan (D-ND), Tom Harkin (D-IA), and to a lesser extent Paul Wellstone (DFL-MN) made up a not-unsubstantial part of the Democratic Party from the Midwest during the 1980s, 90s, and 00s.

Suddenly, politicians and (more damningly) the Democratic Party is suddenly realizing it needs to pay attention to rural interests; that it’s not enough to let candidates go it alone. Hence a suddenly-renewed interest in national investment in rural Democrats.

We’ll see if this is enough to reverse two and a half decades of, at best, lukewarm attention to farm policy and rural interests among national Democrats — but publications from Politico to the Washington Post would do well to stop treating this issue or politicians like Collin Peterson (to say nothing of Tim Walz, a 2018 candidate for Minnesota governor) as oddities or bygone phenomena.

Now, there are issues here. Certainly no Democrat or activist would want to see the groups Peterson lists (women, African-Americans, LGBTQ+, to name a few) take a diminshed role in the party or be steamrolled by rural (read: white, Christian, heterosexual, etc) interests. Moreover, the issue of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and historic role of NAFTA that Peterson notes are issues that the Democratic Party–and, looking ahead to a relevant 2018 gubernatorial race, the DFL (I might start doing that more often)–needs to address. As 2016 laid all too bare, there are a number of endemic weaknesses in the national and state Democratic parties that have weakened their ability to run effective and winning campaigns in rural areas. Moreover, issues of gerrymandering increase barriers to Democrats making inroads with rural interests because fewer of them fall in competitive districts (breaking both ways! Ron Kind, in Wisconsin’s rural/exurban 3rd District, didn’t get a Republican challenger in his 2016 reelection bid).

But let’s not pretend this is a new phenomenon which we have no recent historical frame of reference to understand. Don’t call it a comeback, rural Dems been here for years.

Down-Ballot Elections in the Midwest, 2016

The following are excerpts from a larger panel titled “The New Midwestern Politics? The 2016 Election and Beyond” at the 2017 Midwestern History Association Conference, hosted at Grand Valley State University’s Pew Campus in Grand Rapids, MI, and hosted by the Ralph Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies. Feel free to contact me with questions about the maps, findings, or methodology.

CH

Continue reading “Down-Ballot Elections in the Midwest, 2016”

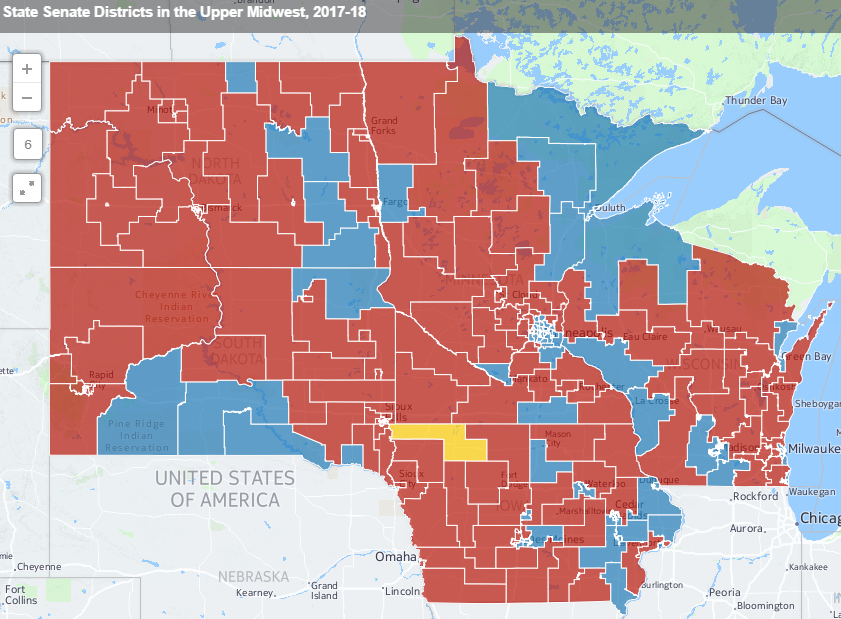

Mapping Party Control of State Legislatures in the Upper Midwest

In preparation for a panel on the Midwest in the 2016 elections for the Midwestern History Association Conference in Grand Rapids this June, I’m working on my particular focus: down-ballot elections. My biggest problem was this–besides saying “things didn’t go well for Democrats,” I had little-to-no idea how to show that (Ted, if you read this, I swear things are going better now).

We talk a lot about the growing rural-urban divide between Republicans and Democrats, but elections within even my lifetime, like 1992 and 2008, demonstrate that a healthy amount of Democratic support came from rural and suburban areas. So where is it now? In order to fully come to terms with the landscape of the Democratic (the focus of my dissertation, thus its emphasis) and Republican parties in 2016, we need to find where they have support at the local levels.

Continue reading “Mapping Party Control of State Legislatures in the Upper Midwest”