How do we find relevance in the New Deal when its sites have changed?

Continue reading “Reclaiming the New Deal: Digital Humanities and Minnesota History”Barnstorming the Midwest: River Falls, WI

What do you do when you need some time off the road but still getting work done? Find an archive under 40 minutes away that has relevant papers!

Continue reading “Barnstorming the Midwest: River Falls, WI”

Reflections on a Semester in the Digital Past

The assignment:

At the completion of the semester, you will write a reflective essay that summarizes your learning and growth during the class. These essays should be no more than 2,000 words. This is a chance for you to process your work and to consider the ways that it will contribute to your future ventures.

This is my last assignment of 2016. We finally made it.

Continue reading “Reflections on a Semester in the Digital Past”

Reviewing other works for HIST 5953 and not understanding the Internet.

Part of our assignment for this week–in addition to continuing to be the diligent and thoughtful students that we’re definitely, totally being on our projects–was to review another student’s website. Without posting the full review here, I was assigned Natalie Russell and Nick Ostermann’s site on the Gens de Couleur. They’re making an intriguing argument about the role free people of color (FPC) played in antebellum New Orleans and in turn demonstrating how they “whitened” themselves in official portraits and correspondence.

My greatest takeaway was the need for identifying and gearing presentation and media used to the audience you are trying to reach. Natalie and Nick had originally identified that they wanted to reach middle- and high-school students, and I think their biography style is a great way to give students something quick but still historically “deep” to read. I’d love to see them play up their primary sources, though, and play down their narrative. Maybe a catalog of the primary sources related to Julien Hudson at the top of the page, before the narrative, would help them do what I struggle with as an instructor–getting my students to actually engage with a primary document. A letter, rather than a portrait, would be even more ideal. While I love playing the “let’s analyze the coloration of American Progress” game as much as the next instructor, there’s something to be said for reading the handwriting and actual words of a wealthy New Orleans FPC.

What this process has challenged me to do is better identify at whom I am targeting my map and the curated newspaper articles in my Omeka. The short answer I had at first was “I don’t know…grad students, probably.” On the whole I think that’s about where my thought process is at, because I don’t think historical electoral politics are getting a ton of people out of bed in the morning. I can better define that, though, and I will have to try and find a way to demonstrate that in my “About” section or my overall argument.

In “Cory doesn’t understand the Internet” news, I figured out Carto yesterday. Seriously, go look at my map. The findings could be wrong, insignificant, or just not that interesting, but I finally was able to make tidy data, upload shape files and datasets, merge them into a map, construct different layers, and display them in a manner approaching efficiency. It was the product of about two weeks of work and about 40 deleted maps and datasets (Carto kept uploading percentages as “strings,” not “numbers,” then deleting them when I’d try to convert them in the dataset), but it felt good to finally have that “Eureka!” moment yesterday.

But this is about what I don’t get about the Internet.

One thing I really enjoyed, going back to the review of Natalie and Nick’s project, was how Natalie embedded her Apple Music in her “About” page. That seems like a fun way to put yourself in the shoes of the scholar you’re reading about. I don’t think people want to listen to a collection of Whitney Houston, “The Planets,” 80s pop rock, the occasional country song, and Big Ten fight songs (shut up), though.

Since this page is a reflection of me both as a scholar and a person, I try to care about what I put on it. Thinking about the “About” section I currently have makes me wonder how well I’m doing that.

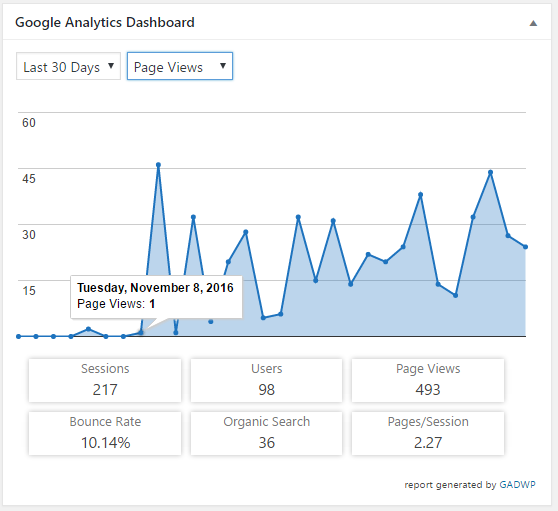

In particular, though, the vain, egotistical man that I am is curious as to whether anyone actually uses my site other than me, Dr. Leon, and my mother (hi, Mom! Sorry you just got my Christmas list). To that end I installed Google Analytics the day after I created my site. It was all pretty innocuous, the occasional spike when I’d do my blog post (up to 3 or 4 if I was lucky!), but nothing exciting. Then the election happened.

I saw that and thought, “Wow! People loved my thoughts on the election and what it means for how we study Midwestern politics going forward!” (And some of us do! Stay tuned for a collection of essays Jon Lauck is soliciting on Midwestern politics that’ll be done sometime before the 2020 election!)

Those spikes since, I told myself, were no doubt because I’d done a great job with SEO on my blog posts and really made things interesting for people looking for reviews of Visualizing Emancipation or the role of Digital Humanities in graduate school training.

Nope.

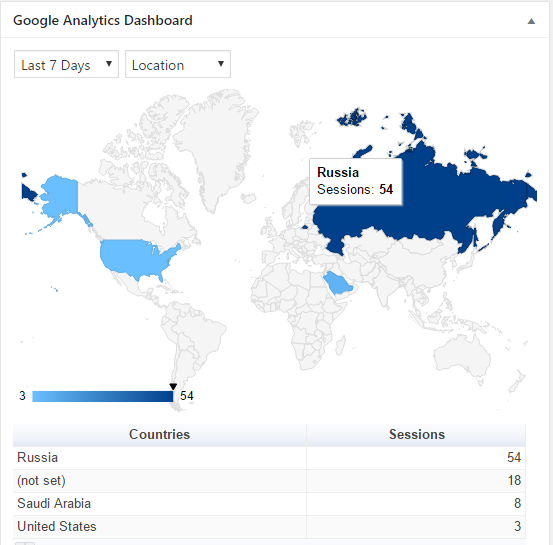

Once I realized I could filter by location, I learned something very, very different: Something or someone based in Russia is hitting my page at very high rates.

Even Saudi Arabia is outdoing my American audience. So Dr. Leon, if suddenly my project goes from African Americans in the election of 1896 to the Great Game or discussions of migration across the Rub’ al Khali, you’ll know why.

Russian and Saudi friends, hi! If you’re hiring a scholar to teach Midwestern political history, I’m your guy. (Yes, I know it’s spam.)

The internet is a weird place.

Reviewing the Marquette Digital Scholarship Symposium

On Tuesday, September 29 Marquette hosted what organizers Janice Welburn and James Marten promised was the second of many annual Digital Scholarship Symposiums. Held in the Beaumier Suites in the basement of the Raynor Memorial Library, the interdisciplinary sessions both charted a promising future for digital scholarship and highlighted the ways in which current Marquette researchers, both faculty and students, continue to use DH in research and the classroom.

University of Virginia Research Associate Professor of Digital Humanities Bethany Nowviskie gave the first keynote address, entitled “Alternate Futures, Visible Pasts.” Dr. Nowviskie highlighted the need for digital humanists and archivists to “design platforms that break the fatalism in historical archives” and position them not as statements of what was, but what can be. Using the concepts of “time’s arrow,” “time’s accountant,” and “the Anthropocene,” she indicted the modern archive for creating and sustaining “projects of retrospect, rather than projects of prospect.” Those projects of prospect, she reasoned, would help sustain movements like “Afro-Futurism,” wherein the greatest example of agency for communities like African-Americans (especially in the context of modern protest movements) are the ability to create an individual philosophical infrastructure.

Following Nowviskie, George Mason Director of Public Projects at the Center for History and New Media and Associate Professor in the History and Art History Department Sharon Leon presented a second keynote address on “Reading Between the Lines: Inquiry-Driven Digital Scholarly Infrastructure.” Opening with a survey of digital collections focusing on the various protests of police shootings across cities like Baltimore and Cleveland, Dr. Leon called attention to her own work on the the September 11 Digital Archive. Using both the September 11 project and her own work with Omeka, Dr. Leon argued for recognition of digital tool-making as academic scholarship, because she and others were “building the platform by which others do scholarship.”

Challenging Ed Ayers’ 2013 assertion that digital scholarship “must do the work we have long expected scholarship to do: contribute, in a meaningful and enduring way, to an identifiable collective and cumulative enterprise.” Building on her discussion of Omeka, Dr. Leon asserted that this attitude was part of a “reinforcing cycle”: Scholars, instead, need to change their conception of what counts as scholarship. Instead, of merely tracing footnotes or replicating research, she argued, scholars need to come to accept “non-narrative interpretive forms” of scholarship as an “equivalent piece of material.”

Returning to Omeka, Dr. Leon noted the importance of Linked Open Data in changing the way scholarship was done. Using the example of “Subject -> Predicate -> Object,” she related how, in visualizations of slavery relationships at Georgetown, she constructed vocabularies of “Francis Nease -> Relationship:EmployerOf -> Priscilla Queen” to map in 2D space the complex social structures of plantations. The “next step” in breaking the reinforcing cycle, Dr. Leon added, was creating platforms like Omeka S which could help adding “modifiers” (prepositions, start/end dates, etc.) which would add chronological and geographical depth and breadth to the 2D model.

A faculty roundtable in which various Marquette scholars shared “Tools and Technologies for Digital Scholarship” followed. Dr. Beth Godbee highlighted the ways in which undergraduate English classes encourage adaptations in digital rhetoric. James Brust of the Wakerly Media Lab highlighted the possibilities of collaboration between humanities and the world of communications, and Elizabeth Gibes of the Digital Scholarship Lab (where I am currently embedded as an intern) noted a number of the different digital tools for the classroom like Tableau and ThingLink. Finally, Dr. James Marten and his interns presented their work on the Near West Side project, which has traced the cultural history of the neighborhood around and west of Marquette, which has incorporated a narrative style to highlighting the lives of various residents of Milwaukee in the early 1930s.

Following a panel including Drs. Nowviskie and Leon, there are a number of important takeaway points for scholars wishing to “do” digital scholarship and universities wishing to support it. On the institutional side, if universities wish to attract young scholars, their faculty will need to abandon the “reticence to do the work to learn how to evaluate the scholarship.” Similarly, digital scholars will need to learn to negotiate when they come into a department what kind of research they are expected to put out, as well as what counts. While institutions need to understand, as Dr. Leon noted, that they merely “can’t put [digital scholarship] on top” of existing research and development, especially for young scholars, those scholars also need to know that they are not learning a technology, but learning how to produce things for that technology.

To be sure, there are potential points of frustration with future generations of digital scholars. Dr. Nowviskie’s sometimes-flippant remarks about the challenges associated with archival research appear either not to appreciate the amount of training and thought put into archival collections or flagrantly disregard the vital need for responsible archivists. Given that staff of the Marquette University Archives were in attendance, the remarks were likely poorly received by some. Digital scholarship must continue to embrace a working relationship with the archive–hardly static, always evolving and changing–as a means of promoting the highest levels of research. To dismiss where scholarship has been merely to embrace the digital would be foolhardy; discussions of how to preserve and embrace the agency of marginalized communities should not reject the archive out of hand. Such characterizations serve not only to further divide the scholarly community but limit historians’ ability to tell the whole story as it happened.