How do we find relevance in the New Deal when its sites have changed?

I’ve documented my Citizen-Historian Project and my own adventures in Minneapolis on this web log in the past: walking, biking, and driving to find historic New Deal sites has been a great way to stretch my legs and, in a classroom setting, engage otherwise-isolated students during COVID lockdowns. This piece serves as Part II–a long-overdue update.

In my two years teaching at St. Cloud State, students have answered this call with an amazing set of archival and community finds: They’ve documented a historic school in Eagle Bend, a now-demolished gym in Lindström, a WPA stamp-hunt in Paynesville sidewalks, a historical marker in St. Cloud, a WPA canal that saved Lake Osakis, a roadside rest stop on the North Shore…the list goes on. These were all from the five total sections I taught of HIST 141 (U.S. History II) — undergrads in a survey course of 25-40 students doing their own archival research and writing a narrative of the site for permanent digital preservation.

Frustratingly, there are as many great projects that never made it to the map: students did archival research from the Iron Range Research Center in Chisholm to Crow Wing County Historical Society in Brainerd but never uploaded their work. One project changed the way I personally think about Civilian Conservation Corps efforts by explaining surveying methodology and showing me actual artifacts held in a surveyor’s office somewhere on the Iron Range. (Jesse, if you read this: you owe me an email.)

It’s been a rewarding process, but the last year of teaching has also forced me to personally grapple with an issue I walk away with after teaching this class session: What use is the New Deal to a modern student?

The site of the WPA-updated public library in St. Cloud is now a Wells Fargo parking lot. The second Robbinsdale High School, built by the WPA in 1936 on 42nd and Regent just a mile from my house, is townhomes. My hometown, Inver Grove Heights, has a WPA-constructed village hall that is still standing…but overgrown with weeds, boarded up, and adjacent to Minnesota’s only full-liquor, full-nudity strip club. (Shout-out to the King of Diamonds and, literally 1000 feet up the hill, my first elementary school.)

My Citizen-Historian Project challenges students to capture the histories of those sites: who built them, when, where, and for how much? More importantly, how did they matter to the community when they were built?

That last question is, I impress upon students, the big one: Whether it’s an Eagle Bend woman confined to a wheelchair recalling how football players would carry her up the stairs at their handicap-inaccessible school, sidewalks in Paynesville showing seasonal work cycles and how a 20-person job could have a massive local impact, or Osakis community members hailing a government project for saving their lifeblood of their community, we’re looking for the meaning of these sites beyond “It helped during the Great Depression” or “We ought to remember history.”

But what use is that history today?

The events of 2020 obviously challenged me and many others (particularly those of us who are white, male, from privileged backgrounds, and so on) in myriad ways. And I write this not to suggest that I found the answer (if only!), but to get my thought process down on some virtual paper.

In my two years at St. Cloud, across my four in-person sections of U.S. History II, I could count the students of color in my classes on two hands. That’s under 10 out of about 150. When we reduce that to students of color who did the Living New Deal project, from an admittedly small sample size I can think of three: one from south-central Minnesota who did a small-town ballfield, another from Minneapolis who looked at the Walker Art Museum’s renovations, and one–a high school student very open about her status as an immigrant–in St. Cloud who looked at an addition to St. Cloud Technical High School.

All three acquitted themselves well, as most students on that project tend to do. But the last of those three experiences has resonated with me. In navigating the history of St. Cloud Tech, writing in her reflection and in a conversation after the class had ended, that young Somali woman talked about “ownership” of Tech — her belonging in a space and community that is predominantly white, while noting how the impacts of those WPA projects are felt today by communities of color.

That, of course, isn’t to erase the very deleterious effects of New Deal-era planning–whether the racialized “dialect” on display in WPA oral histories of formerly enslaved peoples or the now-perpetual discovery and rediscovery of redlining by the Federal Housing Administration–to say nothing of the failure to pass an anti-lynching bill during the New Deal. But a young woman who was a recent transplant to St. Cloud finding ownership in an 80-year-old project stood out to me. Was this her New Deal?

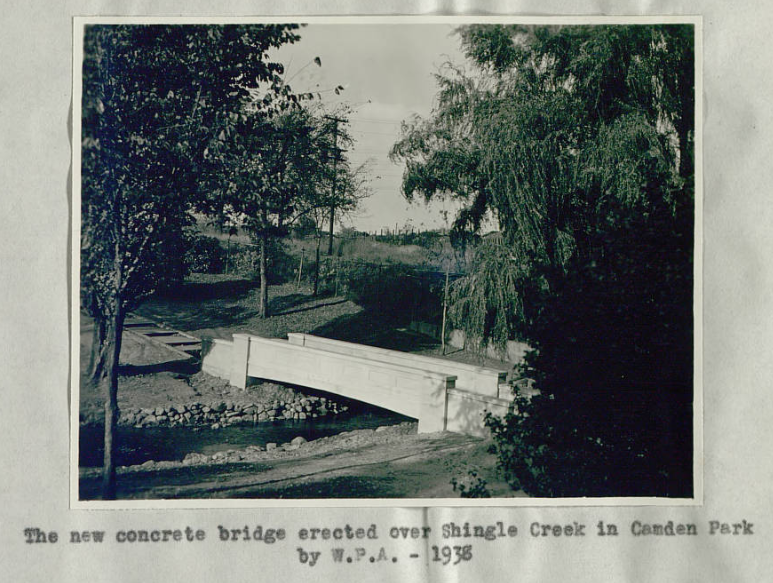

A WPA project I found on my pandemic-time bike rides in March 2020 was a small concrete bridge over Shingle Creek in what is today Webber Park (then-Camden Park, renamed 1939) in North Minneapolis:

Here’s how that bridge looked in 1938:

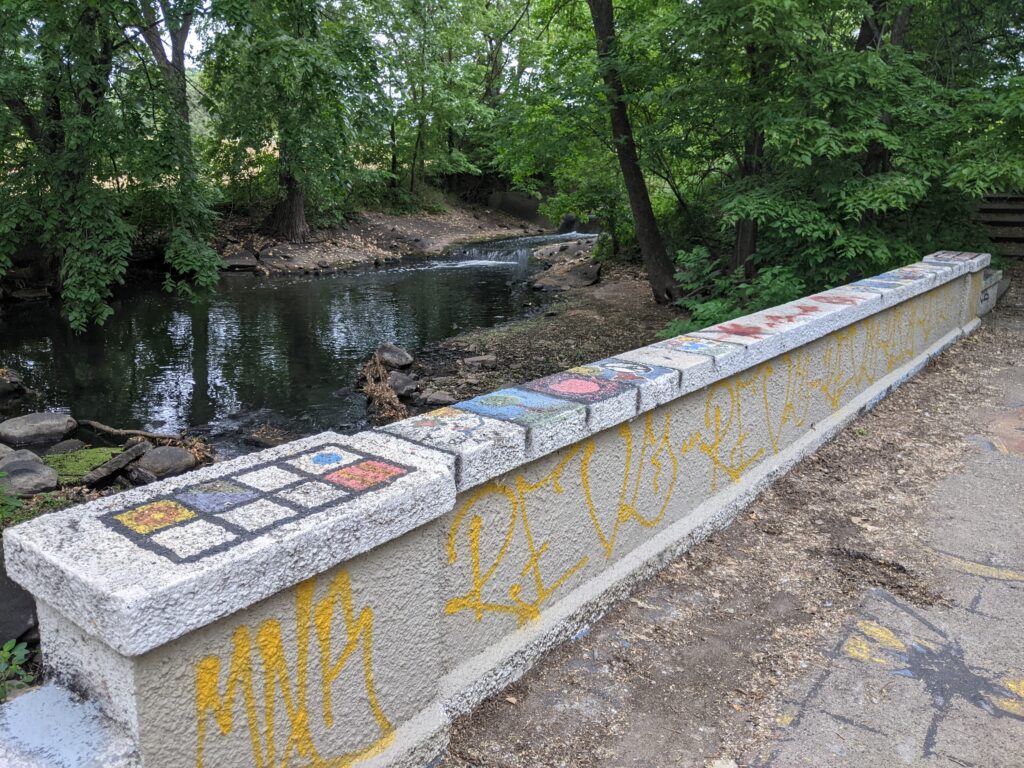

And here’s how it looks in 2021:

I don’t think it takes a forensic expert or a cool JuxtaposeJS to notice: some things have changed–not just from 1938 to 2020, but 2020 to 2021!

You see, this really sexy Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) “Local Historic Bridge Report” on the above “Bridge 93843” detailed how, while the WPA-constructed bridge “retains almost complete structural integrity” (4), some cracking and rotating meant the bridge approaches had “undermined” (9). From this very embarrassing and very sweaty selfie, you can see the differences between the above approach and this one:

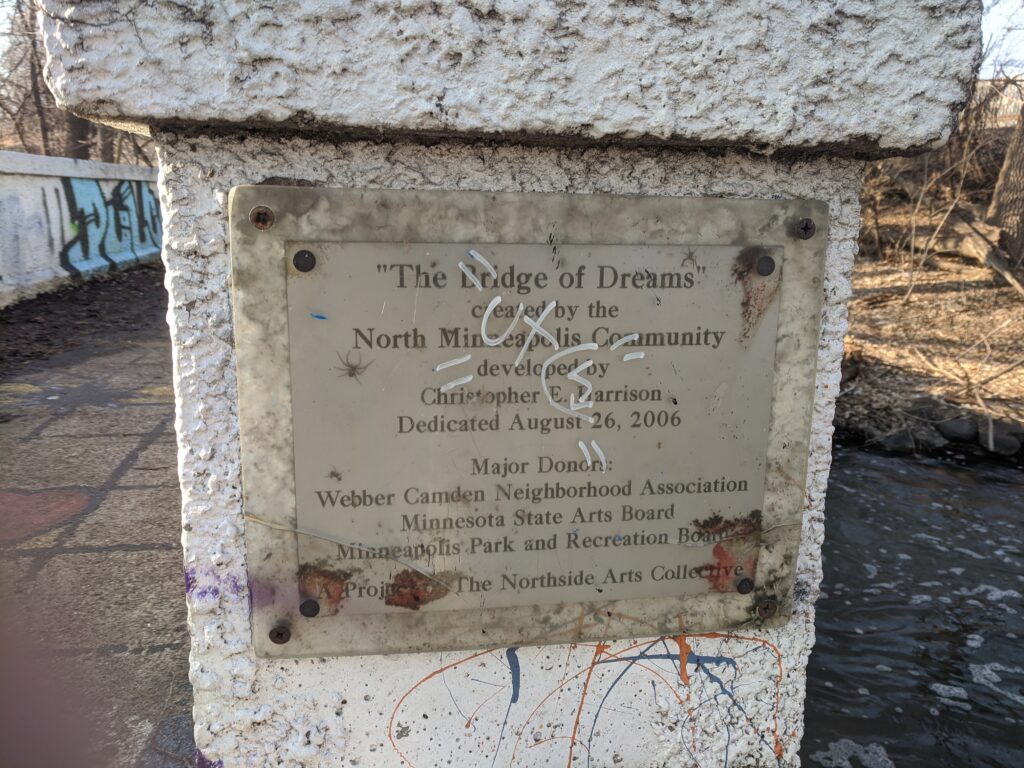

But, as the MnDOT report also notes, “The bridge’s parapet railing, wingwalls, deck, and approach trails were painted in 2006 as a community art project sponsored by several local entities including the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board” (9). While they noted the paint “does not appear to negatively affect the integrity of the concrete below” and recommended it remain in place (21), the south-facing side of the bridge had its colorful paneling and “Bridge of Dreams” logo painted over a neutral gray. And I have not been able to re-locate this plaque:

That plaque points us to this 2006 event led by local artist Christopher E. Harrison:

The Webber Park/Camden neighborhood in North Minneapolis is a community that overflows with activity, joy and a cooperative camaraderie. In my time there, I have found the people friendly and accommodating, the businesses loyal and considerate, and the environment warm and inviting.

So from this, I decided that a project or event that would bring together our neighborhood for something that incorporates the spirit of community, livability and appreciation for the environment that the Camden neighborhood represents.

The whole idea jelled in the form of a painting project. The goal is to have the members of the community decorate the footbridge located at Webber Park in the Camden Neighborhood and transform it into the “Bridge of Dreams,” where members of the North Side community and beyond can paint or write personal messages (dreams or wishes) for themselves or others.

The bridge in Webber Park was old and in danger of being torn down, so this “rehabilitation” would give new life to it and that area of the park.

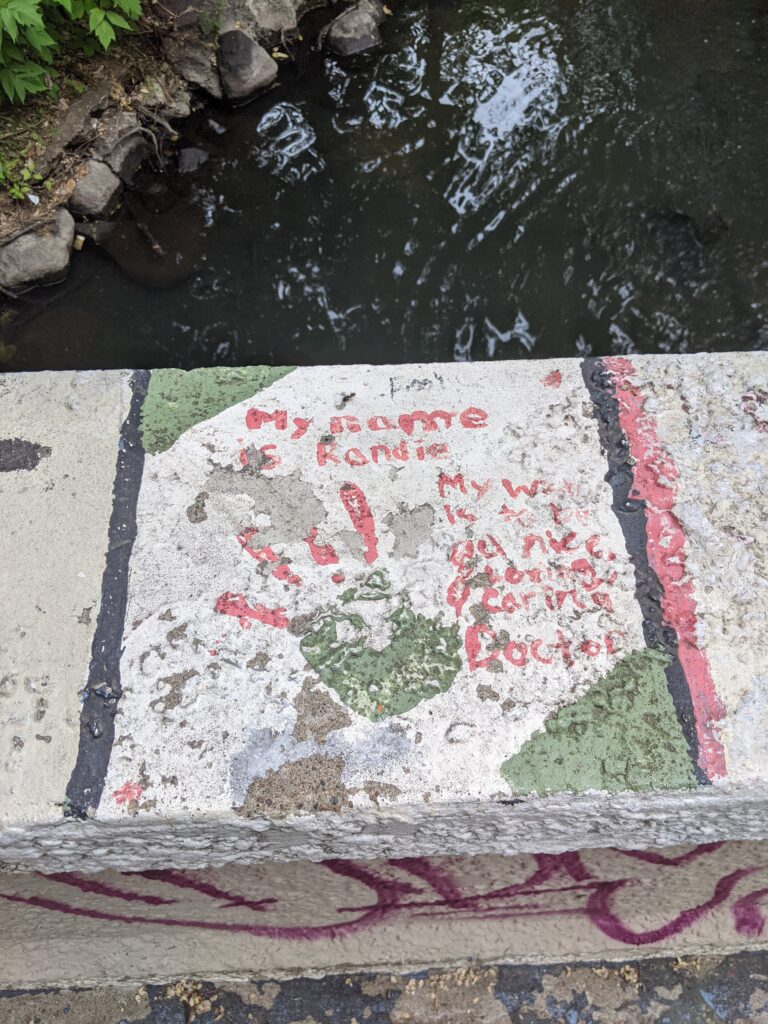

The bridge–“old and in danger of being torn down”–was not necessarily a WPA project: nor did it have to be! In 2006, this WPA project became, however briefly, a site of some new meaning for the North Minneapolis and Camden community. I don’t know how long it will be until the bridge requires more attention (the MnDOT report estimates “20 years or longer” in its executive summary), but the partial erasure of that community event prompted me to photograph some of the community art as best I could:

You can see some very apparent messages: whether pride in Girl Scouts, kids’ love of hockey and martial arts, pie-in-the-sky dreams for “love” or “peace” or “no war”, a hope to “Save Planet Earth”, or a nascent community theater organization in Camden. Who painted these? How old were they? Were they all painted at the same time? Did Randie grow up to be a doctor?

There are stories here that we just might never know, but the Bridge of Dreams is a site where a community took a WPA project–intentionally or not–and imparted additional civic and cultural meaning on it. Sixty-eight years after its construction, the bridge was still a significant enough landmark to merit community action. Eighty-two years on, it was restored through a public project.

And, just a year prior, up the stairs on the west end of the bridge, a homeless or under-housed person had set up a tent and amassed some personal possessions. Quite the juxtaposition, just up the hill from a WPA-constructed bridge:

What other meaning can we find in historic community sites? And, challenging me to think about how I teach these digital projects, how have communities of color–whether in a St. Cloud school or Minneapolis park–engaged or transformed those sites? What meaning do others take from these projects to which I might be blinkered by my own perspectives or privileges?

When discussing augmentations to Webber Park in the 1930s, the Minneapolis Parks history of the site merely notes “Other than some improvements to the creek and playgrounds in the 1930s with federal work relief funds and crews, the park remained essentially as it had been following the 1927 renovation until 1959.” More inclusive projects like the natural swimming pool and rec center are highlighted extensively, and perhaps understandably, but the bridge is not mentioned. Nor, less surprisingly, is the homeless encampment.

Our history of such a simple site is incomplete.

Perhaps it’s not all that simple.

Because it’s not only our history.

This was a great read Cory! Side note: I want the phrase “Photo unfortunately taken by author, March 23, 2020.” on my headstone.