We talk a lot in today’s day and age about the rural-urban divides that plague American politics. But where do those divides come from? Can we pinpoint their genesis?

Now, the obvious answer to that oversimplifying question is clearly “No.” But providing some historical depth to that question is one of the challenges–and goals–of my research.

Part of my reason for asking that question is obvious: The Midwest conjures up imagery of pastoral landscapes, flyover country’s grid patterns, and maybe even an irrigation system on a wheat farm (passive-aggression, too, if that last link is any indication of Minnesota Nice). [There are obviously more things it cues up, depending on your profession and/or point of view: snow, political inclinations, ethnic whiteness and the issues therein… I digress.]

At the 2016 Northern Great Plains History Conference at St. Cloud State University, though, presenting a paper on Rudy Perpich and the rural-urban divide in the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, though, I received an excellent critique from Augsburg Professor of History Michael Lansing that’s stuck with me to this day: What about the suburbs?

I still struggle with this question. The populations of suburban Dakota and Washington counties nearly doubled between 1970 and 1990, Anoka County grew by almost 60%, and smaller counties like Scott, Wright, and Carver all nearly doubled in size to around 50,000-70,000 people. Clearly they were growing forces in Minnesota politics, with mixed political inclinations which, by the 2000s, had become almost universally-regarded as Republican-leaning (Scott, Wright, Dakota, Anoka, and Washington all flipped to the Republican column in the presidential election of 2000…we’ll leave snark about the median income of Carver County for another day). But how did they vote before the days of George W. Bush?

The short answer is that it’s complicated and I’m still working it out. But I have to look for evidence that informs a couple notable events and trends:

- David Minge (DFL) won election to the suburban 2nd District in 1992, replacing Vin Weber (I-R), who opted not to run after being implicated in the House Banking Scandal…

- …which also brought down incumbent DFLer Gerry Sikorski in the suburban 6th. Sikorski lost to rising I-R star and eventual Senator Rod Grams.

- Meanwhile, the suburbs bolted for the I-R’s [eventual] gubernatorial candidate Arne Carlson over DFL incumbent Rudy Perpich in the 1990 election.

- Outside my dissertation, but in 1998 Reform Party candidate Jesse Ventura won the entire Metro area, including pluralities in Hennepin and Ramsey counties (where you can find Minneapolis and St. Paul, respectively).

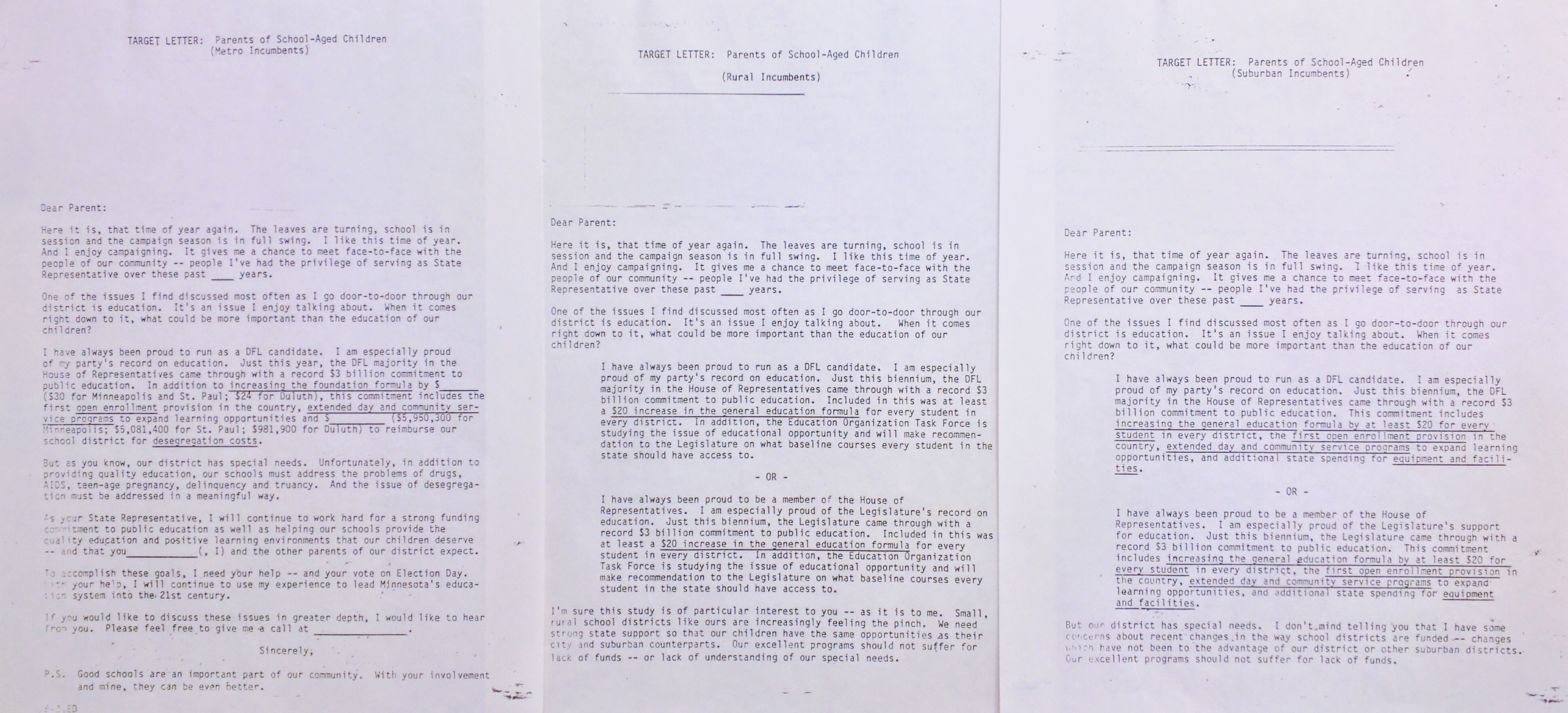

All this brings me back to the issue of (for my dissertation’s purpose) the DFL’s relationship to suburban Minnesota. A couple weeks ago, as I was working (on a Saturday — someone tell Fr. Avella just how devoted I am) in the papers of the Minnesota DFL at the Minnesota Historical Society, I came across some general campaign notes from the 1988 election cycle (Box 53, folder “Campaigns: General Correspondence, 1988). Can you spot the differences?

Here are the points I’m going to work on unpacking in my subsequent research (both on Skip Humphrey’s 1988 U.S. Senate campaign against Dave Durenberger and in other elections):

- The DFL is clearly playing at rural resentment (hi, Kathy Cramer) with the line to constituents of rural incumbents that “our children have the same opportunities as their city and suburban counterparts.“

- There’s a curious use of a lot more dollar figures in the letters to urban constituents and and lot fewer to rural constituents.

- The DFL is very adamant that suburban voters know that their money is also going to help fund suburban schools’ “equipment and facilities.”

What do those things mean? Well, besides the pretty clear pandering to rural voters’ constant fear that their schools were being underfunded at the expense of city schools (who, the “Metro” letter notes, are spending money on desegregation — I would hazard a guess that they’re gun-shy on the race question), there are some inferences to be drawn. DFL candidates are able to give more concrete numbers to Metro constituents, perhaps because more money is going there. The suburban schools’ arms races might have been heating up — I can’t say I’m an expert on whether Minnetonka or Eden Prairie had a nicer computer lab in 1988, but I read in that there’s an “image” issue with suburban educational/political “consumers” wanting bang for their buck.

What’s clear to me is that there’s a real strategy out there, within the DFL, of how to target specific regions. Education is, no doubt, just one arena in which those issues play out. I hope to continue learning–through campaign memos, speeches, publications, polling data, and more–just how DFLers of all stripes hoped to bridge the rural-urban-suburban divides. This is just one example of it in practice.

Finally, looking for those themes in other major suburban areas (particularly Milwaukee, where Tula O’Connell is way ahead of us all, but also Madison and Des Moines) will help add some historical depth to the question of suburbs in Midwestern and national politics. There are already trailblazing books on suburbs and their effects on conservatism in Atlanta, housing in Detroit, and even liberalism in Boston, but I have my doubts as to their universal applicability to the Upper Midwest. We’ll see what I find.