Folks are discovering Minnesota governor Tim Walz’s rural liberalism. It’s part of a deep-seated rural, Midwestern tradition that the national Democratic Party has ignored. Here’s how one bike trip flipped another rural district, like Walz’s, that hadn’t gone blue since the Great Depression.

Whether hailed as “America’s Midwestern Dad” or for his now-ubiquitous claim that MAGA Republicans are “weird”, Tim Walz has nabbed Americans’ attention as a potential vice-presidential pick for Kamala Harris. Observers are taking note, too, of his populist economic bona fides, and wondering if he could win rural Americans’ votes.

That is, indeed, a portion of the country the Democratic Party has supposedly written off. So it makes sense that we would want to understand how and why Walz won those rural voters!*

That’s where I see my role here — not to suggest that you should vote for Tim Walz or that I’m personally endorsing him. Instead, as a historian of Midwestern politics and the Democratic Party, especially rural liberalism, there’s context for the Democratic Party’s once-strength in the rural Midwest that I think you should know about.

Some rural Democrats like Walz bucked the cold economic calculus of the Democratic Party in the mid-2000s. Minnesota Rep. Betty McCollum made headlines in July 2024 for claiming that, when Walz won his first campaign in 2006, Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee chair Rahm Emanuel initially declined to support Walz, saying “He has no money, no nothing.”

In 2024 it also remains a common refrain, assessing rural Minnesota from a national perspective, that these regions have rarely been or will no longer be Democratic DFL blue.*

In Minnesota, the Democratic Party is represented by the Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) Party, formed in 1944 by a merger between Minnesota’s second-strongest party, the left-wing Farmer-Labor Party, and the third-place Democratic Party. The Republican Party was known as the Independent-Republican (I-R) Party of Minnesota after the fallout from the Watergate scandal, retaining that name until 1995. In this article, I’ll use “DFL” and “I-R”, because local stylizations matter.

And so Walz, to some observers, appears to be a rural Democratic whisperer.

My point here is to neither (1) cast aspersions on the tweet above, nor (2) suggest Walz does not in fact have credibility with rural America! Rather, it’s to point out that his rural Midwestern liberalism is one that the Democratic Party actively ignored in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It goes deeper than Walz, stretches across rural America, and has historically represented a vital voting bloc for Democrats, especially in the Upper Midwest.

To show that, I’d like to describe one campaign that demonstrated rural substance and style in the Democratic Party: how David Minge won Minnesota’s Second District, which hadn’t gone blue in fifty years, in 1992.

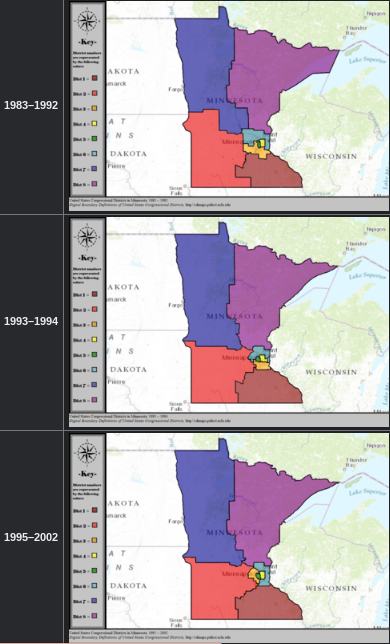

In the interest of fairness to all parties, Walz’s district (Minnesota’s Fightin’ First, covering the southern quarter of the state from western border to east) had not existed in that form in recent memory. Only moderate and now-former DFLer Tim Penny had represented the First as a budget-hawking Democrat from 1983-1995 before retiring, and that district was really southeastern Minnesota, from the south suburbs of the Twin Cities down through Rochester to the Iowa border.

Minnesota’s Second was a tougher nut to crack.

Agriculture-heavy counties in the rural southwest and south-central third of the state, the Second had only been won by a Democrat once since 1914, and that’s when it was districted into labor-heavy South Saint Paul, home to European immigrants who worked in the Armour meatpacking plant. Otherwise, the Second was a conga line of rural Republicans from towns like Glencoe, Redwood Falls, and Truman.

From 1981 to 1993, in particular, the Second was represented by Vin Weber, a Reagan Republican par excellence. He was a budget-slasher, a low-taxer, an anti-union I-R candidate who in 1980, at the age of 28, dispatched a DFL challenger and never looked back, only being modestly challenged once, in 1986, at the height of the Farm Crisis.

You see, Minnesota’s Second District had been disproportionately hurt by the plummeting agricultural economy in the 1980s. Farmers, encouraged in the 1970s to plant “fencerow to fencerow” by Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture, did just that, often mortgaging the farm to do so. When Jimmy Carter embargoed grain shipments to the Soviet Union following its December 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, the house of cards came toppling down: oversupply, deregulation of rail rates, and tumbling property values combined to devastate rural America.

While the Second District was hard-hit by the farm policies of Ronald Reagan, they continued to turn to Reagan Republican Vin Weber–though, at the local level, organizers helped the DFL retake the Minnesota House of Representatives as part of the “Firestorm of 1986”.

So when Weber was caught up in the 1992 House banking scandal* and declined to seek re-election, the DFL had the slimmest of openings.

In 1992 it came to light that the House of Representatives, which operated its own quasi-bank, allowed members to routinely (and sometimes deliberately) overdrawn their own accounts by writing bad checks without penalty. Weber had written 125 bad checks for $47,987.

The problem? Not only was the DFL unpopular in the region, they didn’t really have a strong candidate to run.

Enter David Minge.*

Rhymes with “dinghy”, in case you’re a scandalized Brit.

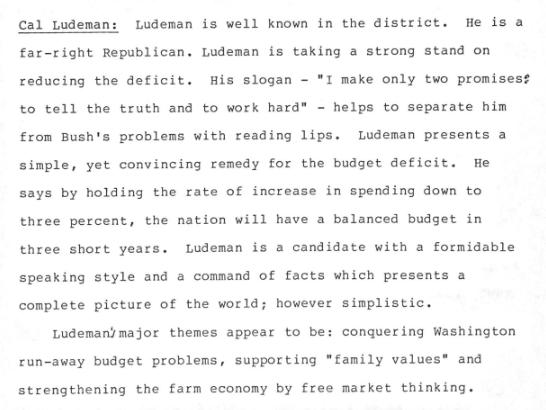

A country lawyer who represented rural energy cooperatives and county banks but had never held office higher than a nonpartisan school board seat, Minge had only 59% name recognition in late June 1992 compared to 87% for his opponent, former state representative, farmer, and conservative Cal Ludeman, who had run for governor (and lost) in 1986.

It was Ludeman’s (conservative) district to lose.

How conservative are we talking? In June 1992 polling, 51% of the district wanted to outright ban abortion or allow it only for rape or incest, though only 21% of voters found that issue singularly-defining. When voters were informed that the choice was between a farmer (Ludeman) or a lawyer (Minge), they went 66-18 for the farmer.

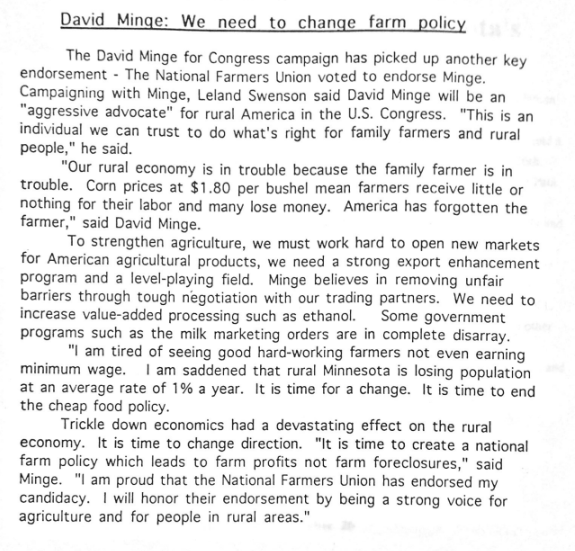

But July polling found Ludeman with severe negatives, particularly on his doctrinaire conservatism that prioritized slashing budgets at the expense of agriculture. And while 56% of voters said they would be more likely to vote for a candidate endorsed by the free-market conservative Farm Bureau, 65% said they would if endorsed by the Minnesota Educators Association, a teachers’ union (compared to just 34% by the AFL-CIO).

The problem? Minge lacked the resources to get his message out there.

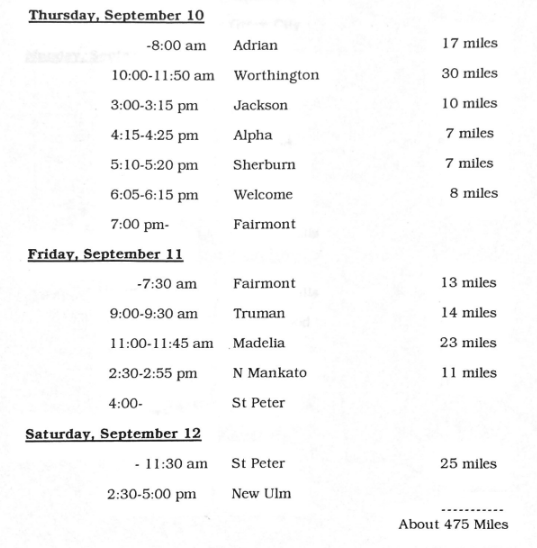

So, despite the fact that his staff had panned a cross-district bike trip as “goofy”, in August 1992 the Minge campaign announced that, beginning on September 4, the DFLer would ride a bike nearly 500 miles across the district.

Beginning in Otsego, then a rural community northwest of the Twin Cities, Minge biked at, frankly, a ridiculous clip across rural Minnesota. Along the way, his campaign took all comers: local radio and newspapers were made well aware of his visit, and the DFLer eschewed few interview opportunities:

That 47-city, 478-mile route “Back to Basics” tour stressed “economic opportunity for all” and “a strong rural economy.” Minge’s campaign team touted that he would “directly meet people in a simple and an old-fashioned way,” blasting local papers with press releases on Minge’s availability and clippings highlighting how his grandfather, Norwegian postman Ole Minge, walked nearly 150,000 miles over his career.

The tour quoted the U.S. Constitution. It promised “Economic Opportunity for All” and a “Strong Rural Economy”. It attacked federal farm policy, alleging it left behind the small family farmers who made up the countryside of rural Minnesota. It rode bikes down country highways and through depressed Main Streets and into parts of the country where election-year photo-ops tend to be not much more than a quick ride in, Serious Discussion with farmers wearing their seed caps, and a well-timed press release.

Minge’s tour again showed Democrats they could win in rural America.

But man, did he put in the work. I’ll bike a casual 20-30 miles on a good day, but take a look at some of the distances Minge was putting in by the end of the trip:

Minge put in 52 miles on Day 1, 59 miles on Day 2, 34 miles on Day 3, 51 miles on Day 4, 58 miles on Day 5, 65 miles on Day 6, a whopping 79 miles on Day 7, 61 miles on Day 8, and 25 miles on Day 9. He shook hands, appeared on local radio, got tons of press coverage, and explained to voters his vision for fiscal responsibility that defended education and small family farmers, backbones of rural Minnesota. It brought together sportsmen and conservationists. It had symbolism. It involved a canoe race, for some reason:

Whether the party establishment would listen, of course, was another matter. As late as mid-September, Minge campaign memos bemoaned “lack of cooperation from DFL at all levels” alongside their own financial and manpower deficiencies.

The bike trip, though, had convinced some elected DFLers outside the party establishment who knew how to win in rural Minnesota. Veterans streamed in from two campaigns that had won rural Minnesota in 1990: Seventh District congressman Collin Peterson, and U.S. Senator Paul Wellstone. By October, Minge was riding with Wellstone on his signature green school bus for campaign stops in blue-collar hubs like Willmar and college towns like St. Peter. “Minge did his best to keep up with Wellstone,” reported John Prusak of the West Central Tribune, detailing a visit they made to the Town Talk Cafe in Willmar.

That folksiness extended into Minge’s approach to policy: down-to-earth, but uncompromising on policies he believed would help the little guy. At an October 24 debate, when Minge compared Ludeman’s insistence on a balanced budget through tax cuts was “like going out in the woods and telling the chipmunks to be quiet.” He paired that with attacks on the price of corn ($1.80 a bushel) and the George H.W. Bush administration’s failure to take a stronger stance at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. He didn’t hesitate to talk tax hikes — and even won the support of I-R county chairmen like John Farrell of Wright County.

Minge won. By 569 votes.

It was a strange win: Minge led among voters’ party identification by late September, but Ludeman had the resources and the connections in southern Minnesota. Everyone knew who he was. His wife was literally “Miss Tracy”, a pageant queen from a southwestern city. The Republican should have won — as Star-Tribune columnist Jim Klobuchar noted, “Democrats win congressional elections in southwestern Minnesota as often as hippos migrate to Lake Shetek.”

Could it last? Minge losing in 1994’s “Contract with America” red wave was certainly a possibility: of the 81 freshman Democrats newly-elected in 1992 or 1993 special elections, 17 lost their re-election bid.

Minge instead won an outright majority, 52%. He increased that total in subsequent 1996 and 1998 triumphs before losing by 155 votes in 2000.

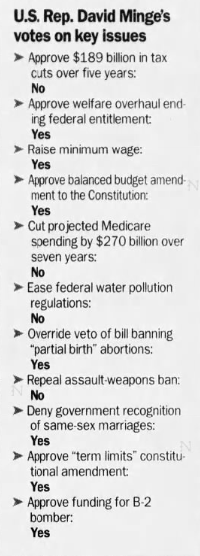

I should emphasize here, again, that policy mattered: Minge campaigned and was regarded as a moderate, “fiscally responsible” Democrat, not unlike his DFL compatriot to the east, First District Rep. Tim Penny (the two co-authored an April 2024 editorial calling for “no sacred cows” when it comes to solving America’s debt crisis).

But Minge gave us a window into the style of Midwestern liberalism that, in the 1990s, helped rural DFLers and Democrats win: he voted against NAFTA alongside Seventh District Rep. Collin Peterson, in contrast to Penny. He voted against House Agriculture Budget Reconciliation Committee cuts in May 1993 “because the reductions fell disproportionately on moderate size farm operations and no part of the legislation attempted to make farm programs workable or farmer friendly” (“Research Overview”, 1994, held at MNHS). He especially voted against the 1996 “Freedom to Farm” bill that brought free-market “reforms” to American agriculture and accelerated the death of small-sized family farms. Even when Minge joined the Peterson-founded Blue Dog Coalition in 1995, he argued that tax reductions should not come until the federal budget was balanced, rather than the other way around.

Tim Walz wouldn’t move to Minnesota until 1996, two years after he married his wife Dawn, from the Mankato area. A few years later, with the substitute social studies teacher and defensive coordinator at the helm, Walz’s Mankato West Scarlets would win a Minnesota Class AAAA state football championship. But Minge wasn’t even his representative — Republican Gil Guteknecht, who succeeded Tim Penny in Minnesota’s First District, was.

So how are the two connected?

First, that they both won in rural southern Minnesota ought to be relevant; if anything, Minge’s southwestern pie piece was more conservative than Walz’s southern quadrant. And on policy, take Walz himself, who has discussed his evolution on things like gun control and immigration. But both went to events like Farmfest and talked the need for “fair trade” and support for family farmers.

Second, both intersected with Paul Wellstone, the progressive populist senator from Minnesota who popularized being from the “democratic wing of the Democratic Party” and frequently poked his finger in the eye of the Democratic establishment. (Indeed, it’s weird for me that some have reacted with a “pigs flying” gif to the news that Bernie Sanders endorsed Tim Walz for vice president, when Walz in fact learned rural campaigning from Wellstone’s campaign management!)

The latter connection, in particular, is important: from his 1990 victory, Wellstone established the Wellstone Alliance, a grassroots group that hoped to transform the Minnesota DFL.

Wellstone’s rise led to uncomfortable moments with DFLers like Tim Penny, who warned that if the Wellstone Alliance controlled the DFL, its “agenda and objectives would become too narrowly defined. It would alienate an awful lot of voters…and over time we would lose more races than we would win.” Penny appeared to be vindicated when Wellstone’s endorsed Senate candidate, Ann Wynia, fell flat in 1994, as did the DFL candidate for governor, John Marty. Or perhaps it was centrist wish-casting: Wellstone won re-election in 1996, as Minge continued to do until his 2000 defeat. Penny left the DFL, running as the Independence Party candidate for governor in Minnesota, winning 16% of the vote in 2002. But those are stories for another day.

After Wellstone’s death, the group Wellstone Action (led by former campaign manager Jeff Blodgett) began training activists in rural organizing. Walz is an alumnus–his lieutenant governor, Peggy Flanagan, trained him–as are a host of state and local officials from Iowa congressman Dave Loebsack on down. A recent post I made on Twitter got a dozen or so responses like “man, remember Camp Wellstone?”

Minge embraced that Wellstone style: he “put in the work,” as Prusak of the West Central Tribune put it in his November 6 recap of the race. The DFLer “couldn’t match Ludeman dollar for dollar. So instead he outworked the farmer from Tracy”: Minge’s “human billboards” eagerly waved signs at busy intersections, and allies like Wellstone and even Hillary Clinton made campaign visits to exurban towns (24 years is enough time to forget how to do that, evidently).

David Minge’s 1992 bike trip erased many of the deficits that rural Democrats faced even following the Farm Crisis, in which Reagan-era economic policies flattened the heartland. It built his name recognition, introduced DFL/Democratic ideas, and showed that Minge would go great lengths to reach the voters of Minnesota’s Second District. Broadly, it was reminiscent of the historically-progressive, stylistically- and politically-populist traditions of the Upper Midwest. Organizations like the Wellstone Alliance (and later Wellstone Action) bridged the years from David Minge to Tim Walz. And their efforts, in the process, reveal a longer lesson for students of American political history: people-first politics helped Democrats win the rural Midwest.