As my students work on their final Citizen-Historian Project (read more here), I feel like it’s only fair that I participate with them. So let’s hit the Internet, hit our bikes, and log some New Deal sites around Minneapolis for the Living New Deal project!

Continue reading “WPA, Then and Now: Digital Humanities and Minnesota History, Pt. I”Rural/Urban/Suburban Divides: Spot the Difference!

We talk a lot in today’s day and age about the rural-urban divides that plague American politics. But where do those divides come from? Can we pinpoint their genesis?

Continue reading “Rural/Urban/Suburban Divides: Spot the Difference!”

Changes to the Wellstone Action Foundation: Paul Wellstone’s Legacy and the Minnesota DFL

What was, in February, an issue among Minnesota DFLers and progressives has suddenly become emblematic of the debate happening nationwide; this time, it centers on the legacy of Paul Wellstone and the Wellstone Action Foundation.

MinnPost, MPR, and national outlets made news in mid-February with reports that Wellstone’s two sons, Mark and David, had been voted off the governing board of the progressive action organization which, according to its past mission statements, worked at “advancing progressive social change and economic justice.” As a Politico report released yesterday reveals, though, then-WAF board member Rick Kahn had raised concerns when the tax filing for the WAF for 2017 showed that mission changed to “advancing progressive social change and economic, racial, and gender justice.”

The Wellstone brothers, according to that Politico report, are now calling for the Wellstone Action Foundation, which MPR estimates has trained over 90,000 candidates and campaign managers for everything from school board to Senate elections, to drop “Wellstone” from its name. Major donors, including the Soros Foundation, have also apparently expressed concerns about funding the organization moving forward.

My intent in commenting on this is not to wade into the waters of adding “racial and gender” to the kinds of justice the new, Wellstone-less board of the WAF wishes to pursue; rather, I’d like to explore (briefly, because I can’t give away the whole farm before I write my dissertation) the coalition Wellstone envisioned and built. That coalition embraced a “big-tent” approach to economic populism which embraced educating DFLers and Minnesotans on a broad range of issues; bridged trans-religious, -racial, and -regional divides; and culminated in a populist sweep to the U.S. Senate in 1990.

After his losing campaign for State Auditor against Independent-Republican and eventual governor Arne Carlson in 1982, Wellstone turned his focus to deepening activist organizing and education within the DFL. This was, for reasons I detail at greater length in my MA essay and will write a lot about in my dissertation, a significant shift; the DFL’s 1982 convention had featured strong tensions between left-wing activists like the DFL Feminist Caucus, the State Central Committee, and the party’s rank-and-file members. Wellstone, in a letter to prominent DFLers, called for “A DFL Issue Oriented Education Foundation,” which he wanted to “address itself to a whole range of vitally important (and sometimes very complicated) questioned ranging from the nuclear arms race, toxic waste dumps, education, farm, labor, iron range, and urban economic problems.”[1] This group, which would of course be based around the wholesome “dinner (pot-luck) and debate series,” was to include “a farm/labor, urban/rural speakers exchange of party activists,” which would create an issue-oriented program to “help facilitate more grassroots involvement in developing our state DFL platform.”[2]

Throughout the 1980s, Wellstone worked to ensure that any crisis in Minnesota politics, whether economic, social, or political, brought with it an opportunity for interreligious, rural/urban, and interracial organizing. After the 1984 elections, during which DFL candidate for Senate Joan Growe was buried by Rudy Boschwitz and Minnesota gave its electoral votes to Walter Mondale by the slimmest of margins, Wellstone blasted the party for “trying to appeal to the same affluent, white, male constituency as the Republicans” and making “no real effort to mobilize the electorate from below and no appeal to families with incomes below $30,000…”[3]

For Wellstone, whether the DFL would join him or not, this translated to action. During the Hormel P-9 strike in Austin, Wellstone walked the picket lines with the striking workers. That August, he and two prominent Twin Cities activists and professors, Peter Rachleff of Macalester and Tom O’Connell of Metro State, sent a letter to communities of faith in the Twin Cities asking if they could raise food and money for the strikers, along with if they would “be willing to take workers into your home while they canvass the twin cities [sic] community.”[4] Wellstone wrote that fall of how he, as a Jew, used this organizing (with groups like Groundswell) in rural areas to combat right-wing extremist and build relationships with Minnesotans on farms and in factories: “In the same breath, the people who feed the nation can be romanticized and viewed as ‘backward,’ unable to make it in the real world of today’s agribusiness. Usually, though, they are out of sight and out of mind.”[5]

This was, of course, put into wide-scale political action in Wellstone’s victorious campaign for Senate in 1990. You can read a pretty good write-up of Wellstone’s quirky campaign here, including the repeated analysis that Wellstone ran as–gasp–a populist. You can see the tensions within the party, though, as former Saint Paul mayor George Latimer quipped that “We’ll have years ridding Paul of his populist notions.”[6] Those “populist notions,” though, were exactly how Wellstone campaigned and how he intended to govern.

He had pushed the DFL to use the lists of Jesse Jackson delegates from the Rainbow Coalition in the 1988 campaign, citing a claim that “No Rainbower was thanked for efforts made in behalf of DFL candidates throughout the campaign.”[7] Wellstone had co-chaired the Jackson campaign in Minnesota, making his indignation even more understandable. But his point, partisanship aside, stood: the DFL needed to be more inclusive of all voices, committed to activism and organizing around economic and social populism.

That Wellstone, long ahead of his 1990 run, had spent the better part of two decades involved in Minnesota activism and organizing is unsurprising to most readers of this blog. But given the debates surrounding the future of the Wellstone Action Foundation, it’s worth considering the “big-tent” language Wellstone consistently used, both internally to the DFL and externally to both activists and Minnesotans more broadly. He built a cross-racial, rural-urban, farm-labor, blue collar-white collar alliance which stunned Rudy Boschwitz in the 1990 U.S. Senate election. Even after his untimely death, Wellstone remains, as Politico notes, the “touchstone for the progressive cause.”

Just last October, on the anniversary of Wellstone’s passing, the Humphrey Institute at the University of Minnesota hosted an event headlined by Elizabeth Warren, Keith Ellison, and Walter Mondale titled “The Democratic Party at a Crossroads: The Wellstone Way and Economic Populism.” At that event, Duluth DFLer Jennifer Schultz argued that “whether another Wellstone comes around or not, Democrats need to go back to his strategy to win,” and 8th District (that’s the Iron Range congressional district, where Wellstone became “tuteshi,” or “one of us,” as Range historian Pam Brunfeldt has noted) DFL Chair Justin Perpich (there’s a name!) implored those present that “the way to regain his energy and make sure we are moving forward is to focus on the economic populism.”

With the DFL facing a critical election this fall in which two Senate seats and the governorship are up for grabs, groups like the Wellstone Action Foundation are central for liberals and progressives seeking to win elections. A split in the DFL between progressive and moderate factions is something that the party can ill-afford. DFLers, no doubt, remember what happened the last time that was the case.

Edit: I neglected to publish the WAF’s February blog post describing its “Next Chapter,” which includes a statement that “An important next step in this process is that we’ve made the decision to undergo a full organizational rebrand. This process won’t happen overnight — we’ll spend deliberate and intentional time over the next year thinking about our story, our community, and our place in the movement as we write this new chapter together. This means we’ll have a new name, a new look, and most importantly: we’ll have an updated identity that reflects the fullness and depth of the thousands of hearts and minds that have influenced this work over the last decade.” Read the full statement here.

[1] Paul Wellstone, “A DFL Issue Oriented Education Foundation,” June 29, 1983, p. 1. Box 1, George Latimer Papers, Minnesota Historical Society.]

[2] Ibid, 1.

[3] Paul Wellstone, Memo to DFL members, December 26, 1984, p. 3. Box 16, “Strategic Planning and Vision, 1984-1990” folder, Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Minnesota State Central Committee Records, Minnesota Historical Society.

[4] Paul Wellstone, Tom O’Connell, and Peter Rachleff, “Dear Friends,” August 18, 1985. Box 1, Peter J. Rachleff, Papers relating to Hormel strike support groups, Minnesota Historical Society.

[5] Paul Wellstone, “Turning rural anger into positive political action,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, September 1, 1985, 7A.

[6] Charles Trueheart, “Paul Wellstone, Odd Man In,” Washington Post, November 14, 1990. Accessed at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/11/14/paul-wellstone-odd-man-in/ddb09796-2d66-4d60-ac37-e5c16c4e41fb/?utm_term=.d61bf59e8cc0. For a blow-by-blow account of Wellstone’s 1990 campaign, see Dennis J. McGrath and Dane Smith, Professor Wellstone Goes to Washington: The Inside Story of a Grassroots U.S. Senate Campaign (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

[7] Paul Wellstone to Lynn Anderson and Ray Bohn, attached to a memo from Bohn to Anderson, “DFL Communications Strategy,” December 12, 1988, pp. 3-4. Box 9, “DFL” folder, Governor Rudy Perpich Papers, Iron Range Research Center Manuscript Collections, Chisholm, MN.

PJ Fleck, “HYPRR Elite,” and the Misuse of Minnesota History

Yesterday Minnesota Golden Gophers football went live with a new website revealing their new uniform colors and branding for the 2018 season, promising to embrace the past while creating a new future of Gopher football. Their embrace of the past, however, is lukewarm at best, hilariously misguided at worst.

Continue reading “PJ Fleck, “HYPRR Elite,” and the Misuse of Minnesota History”

Al Franken’s Impending Resignation and the 40th Anniversary of the Minnesota Massacre

Amid calls from dozens of Democratic lawmakers in Washington for Minnesota Senator Al Franken (DFL) to resign in the wake of allegations of sexual assault and harassment, the Minnesota DFL must tread lightly in the upcoming months as it faces the potential for contesting three statewide elections in 2018 if Franken resigns.

In addition to Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s re-election bid and the wide-open DFL gubernatorial race, a special election for Franken’s seat (again, this is all predicated on him resigning) would set a course for a wild 11 months in the North Star State.

And, even more unkindly for the DFL, there’s some bad historical precedent.

We’re coming up on the 40-year anniversary of the “Minnesota Massacre,” the elections of 1978 in which DFL sort-of-incumbents Gov. Rudy Perpich and Sen. Wendell Anderson went down to defeat, and Bob Short lost a special election to replace the deceased Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey.

You see, none of those positions–Governor or either Senator–was held prior to the election by the man or woman elected to fill it:

- December 30, 1976: Vice President-elect Walter Mondale resigns his Senate seat, and sitting Governor Wendell Anderson makes a deal with Lieutenant Governor Rudy Perpich. Anderson resigned as governor, and Gov. Perpich appointed him to fill the Senate seat through 1978, when Mondale would have been up for re-election.

- January 13, 1978: Senator Hubert H. Humphrey dies, and Perpich appoints his widow, Muriel, to serve his term until a special election would be held in November 1978. This replacement for Humphrey would serve out his term until 1982.

Well, Minnesota Independent-Republicans (a much more moderate bunch back then) did not take kindly to these elite DFLers’ scheming. Worse yet for the DFL, its liberal and conservative wings, sometimes (but not always!) divided along Metro/outstate lines, were fracturing over a number of hot-button issues: the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, the Power Line controversy, and an abortion law which prohibited taxpayer-funded abortions unless the life of the mother was in danger. (You can read an excellent 2008 MinnPost piece on it, too.)

This first came to a boil in the battle for the U.S. Senate seats. Iron Range DFLers came to the June convention angry at environmentalists’ support for the BWCA bill, which would restrict motor use (including snowmobiles and motorboats) in a vast swath of northern Minnesota wilderness. Along with anti-abortion and gun rights activists in the DFL, this conservative faction supported Sen. Doug Johnson, a surrogate for businessman Bob Short, and held off the endorsement of liberal congressman Don Fraser (D-Mpls) for three ballots.

In the September primaries, aided by a large turnout among rural voters, particularly on the Iron Range, and a substantial Independent-Republican crossover vote, Short narrowly defeated Fraser to take on Dave Durenberger in the general election. Perpich gave up over 100,000 votes to the Farmer-Labor Association-supported Alice Tripp, a power line activist unhappy with the state’s supposed “railroading” of environmental and farmers’ concerns. Anderson’s approval ratings, already low, continued to plummet, though he avoided a real primary challenge.

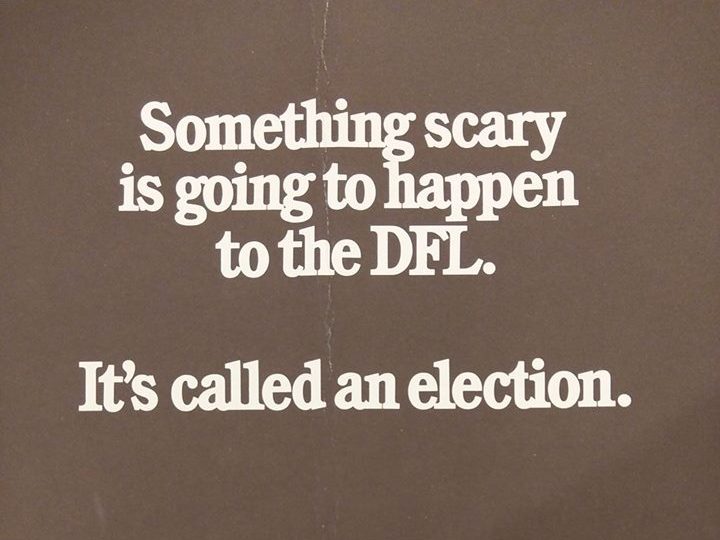

Flash forward to November. This anti-incumbent, anti-DFL sentiment boiled over across the state. The election was preceded by nasty campaigning, as pro-life I-R activists flyered windshields outside Sunday church services on November 5, accusing Anderson and Perpich of being pro-abortion (Perpich was a devout Catholic and had signed the 1978 abortion restriction bill, but when have facts gotten in the way of a campaign?). The I-R itself campaigned across the state on one of my favorite slogans ever:

“Something scary is about to happen to the DFL. It’s called an election.”

Only three state constitutional offices staffed by DFLers survived the Massacre: Attorney General Warren Spannaus, Secretary of State Joan Growe, and Treasurer Jim Lord. Rudy Boschwitz pummeled Anderson, 56-40, to assume one Senate seat, and Dave Durenberger whipped Short, 61-35, to take the other. Perpich, the son of the Iron Range, lost a closer race to conservative U.S. Congressman Al Quie, 52-45, dropping both Hennepin and Ramsey counties and all the suburban counties except Anoka. Boschwitz would serve until his defeat by Paul Wellstone in 1990, Durenberger declined to run for re-election amid scandal in 1994 but was replaced by the I-R’s Rod Grams through 2000, and Perpich took back the governorship from Quie in 1982.

Now, I should reiterate: Recounting this and pointing out its importance is all predicated on the likelihood that Al Franken resigns his Senate seat.

While Franken may be exiting the Senate under very different circumstances, though, the perils of three open statewide seats should be apparent to DFLers in Minnesota. There are still vocal coalitions in Minnesota politics, including the Iron Range and now a much more outspoken urban constituency in the Twin Cities. Adding politics of gender and the current climate surrounding allegations of sexual assault and impropriety to them will only dump fuel on the fire. The DFL has historically…struggled with those challenges.

Being an historian-in-training, I’m even worse predicting future events, but with a crammed gubernatorial field, an open Senate seat may allow the party to vent off some of its internal pressures and run two qualified candidates for two open seats, rather than eating its own in a hotly-contested primary. From various sites including MinnPost and Ballotpedia, here are the DFLers considering or officially running:

- Chris Coleman, Mayor of Saint Paul

- State Rep. Tina Liebling (DFL-Rochester)

- State Rep. Erin Murphy (DFL-Saint Paul)

- State Auditor Rebecca Otto

- State Rep. Paul Thissen (DFL-Minneapolis)

- U.S. Rep. Tim Walz, with running mate State Rep. Peggy Flanagan (DFL-St. Louis Park)

- Potential: State Rep. Tom Bakk (DFL-Cook)

- Potential: Attorney General Lori Swanson

I like Coleman and Walz to emerge from this process, though if the Iron Range flexes its muscle behind Bakk in the process, things could heat up in a hurry. That, of course, does nothing to answer the question of whether a woman should run for Franken’s seat (and there’s a very compelling case for “yes”), in which case Otto or Swanson would likely have more name recognition, but it’s anyone’s guess.

The Republican side is…wide open, to say the least. The GOP’s gubernatorial candidate in 2014, Jeff Johnson, has declared for governor again in 2018, as have State Rep. Matt Dean (R-Dellwood), former Republican Party Chair Keith Downey, and a handful of other state representatives and senators. Lurking off in the distance are more prominent GOPers like Speaker of the House Kurt Daudt, State Sen. Karin Housley, U.S. Rep. Erik Paulsen, and…even Tim Pawlenty?

Time will tell.

But while the circumstances of three statewide elections have changed, including Klobuchar’s incumbency, a wildly unpopular and un-Minnesotan president, and vulnerable incumbent U.S. Representatives like DFLer Collin Peterson and Republican Jason Lewis; there is precedent for understanding these tumultuous times in Minnesota politics.

Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Biwabik Edition

While my last trip to the Iron Range was doubly-immersive, acclimatizing to both the politics and the culture of Minnesota’s Northeast, this one took on more of a “business trip” feel. This was both good, because I explored the deteriorating relationship between Perpich and the DFL, and frustrating, because it provided fewer outlets when things really got confusing.

Continue reading “Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Biwabik Edition”

Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Lake Vermilion Edition

This was an unhealthy trip. And not because of the local beer, porketta, potica, and pasties.

Continue reading “Barnstorming the Midwest: Iron Range, Lake Vermilion Edition”